Computation Modeling

In this blog you will learn the basics of computational modeling. Specifically you will learn:

- What is a computational model and why they are useful?

- How to implement a computational model with an example.

- How to estimate model parameters

- How to evaluate your models performance

Prerequisites:

- Read through this paper or have some basic background in behavioral economics / learning literature (e.g., reinforcement learning)

- Some basic experience with data analysis

What Even is a Computational Model

A Computational Model is just a mathematical equation, serving as a hypothesis, for some psychological phenomenon. We use models all the time. Most commonly, the linear model used for regression. A computational model just adds flexibility because it is not predefined, so you can adjust it to your specific situation. So you can allow it to have some non linearity or have multiple components.

Note: When you use linear (or logistic) regression to prediction choices, you are using a model for how people are making those choices. Whatever you include in this model is all that it knows; and importantly, these models assume a particular structure for how choices are made. Is it the right structure for your data, maybe, maybe not? That is when computational models come in. You get to specific the structure.

Why Should You Use A Computational Model

Implementing computational models require a lot more work than a standard model, so if you are going to use it over standard statistical methods you should have a good reason. There are several reasons one might elect to use a computational model. For brevity, I will focus on two: Utility and Generalization. Of course if you already are familar with their utility, feel free to skip to the next post.

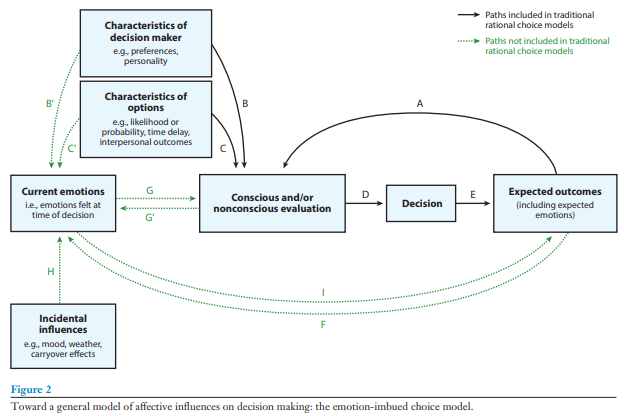

Computational models are particularly useful when they replace older schematic based models like the one below. Schematic models are a hypothesis or rather series of hypotheses about a particular phenomena. These models represent different variables of interest as boxes and relationships between them with arrows. Schematic models are really useful when you are first exploring a feild, and you are beginning to map out all of factors that are relavent to what you are studying. However, these types of models have some significant drawbacks.

Note: I will be specifically, critquing the EIC model, but this was incredibly important at the time. I am specifically using it as an example, but all schematic based model have these pitfalls.

First, schematic based models do not provide specific hypotheses, making them difficult (if not impossible) to falsify. For example, each box on the schematic often represents a plethora of variables. In the EIC model (see below), there is box representing the characteristics of the decision maker (e.g., preferences and personality), which influences both one’s current emotions as well as the utility calculation of the options. Undoubtedly, the authors do not imply every characteristic impacts one’s affective state and utility calculations, but which ones are important, and which can be ignored, are not specified. Perhaps more importantly, because the particular variables of interest are not specified, one would need to test all possible characteristics to falsify the model’s hypothesis.

The second shortcoming of schematic based models is, by design, they do not make specific hypotheses about the magnitude of effects between related components nor do they address the structure for that relationship. For example, in the EIC model, one’s current emotion influences the evaluations they make, which in turn affects their choices. But how much does one’s affect impact their evaluations and what is the nature of that relationship? Is it linear, the more intense the emotion the larger the effect, or is it based on a threshold, where any emotion intensity after the threshold will have a similar effect and any emotion below the threshold will not impact the evaluation at all? Schematic based models do not provide this information.

One solution to these problems is to use a computational model for how people make decisions. In addition to several practical benefits (e.g., ensuring your trial space is sufficiently wide and simulations), computational models address the limitations of schematic based models. Since a computational model specifies all the variables that are hypothesized to impact one’s choice, anyone who has the model can make predictions outside the context for which the original model was developed. For example, if an experiment includes lotteries with win rates of 25%, 50%, and 75%, one could use the model to hypothesize how a person would choose if the win rate was 10%. They need only supply the arguments for a specific lottery as well as person’s parameter estimates.

Crucially, if new experimental data stands in conflict with the a priori predictions of the model, then the model is inaccurate (or at the very least incomplete). There is a clear falsifiable hypothesis even outside the context of the original experiment. Additionally, since a computational model is essentially a mathematical formula, the equaition provides clear, mathematically defined impacts on the outcome; the impact can be interpreted before any experiment or parameter estimation. By design, the model’s formula describes the magnitude for the effects, whether they be linear, exponential, etc. Together, these features help improve the scientific discourse.